Here is a fragment of Danowski & Viveiros de Castro's 2014 book, "Há Mundo Por Vir? Ensaio sobre os meios e os fins" (Is there any World to come?) in which they discuss the Anthropocene and Amazonic indigenous cosmology (they have already passed through many "ends of the world"). Also, they make a good critique of the correlacionism discussion (Meillassoux, Brassier, etc.). It's in this text an passant but it's better discussed on the physical book (I'll transcribe or scan these pages in order to post them on the blog soon).

Deborah Danowski & Eduardo Viveiros de Castro

Translated by Rodrigo Nunes

Deborah Danowski & Eduardo Viveiros de Castro

Translated by Rodrigo Nunes

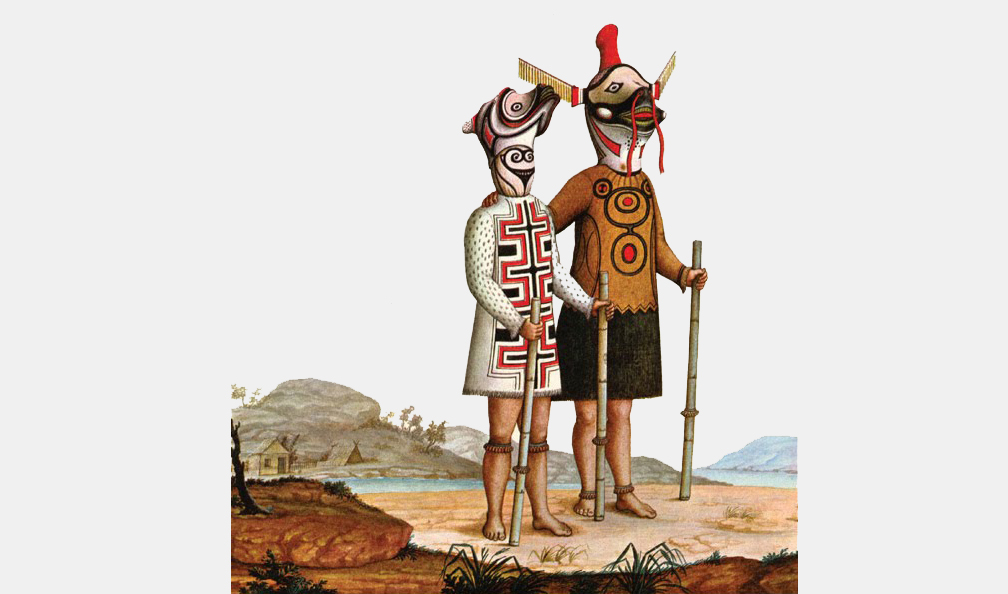

Drawing of two masked Jurupixuna Amerindians, a now extinct Amazonian tribe, registered during Alexandre Rodrigues Ferreira’s naturalist expedition to the Amazon (1783–93) for the Portuguese crown.

The problem of the end of the world is always formulated as a separation or divergence, a divorce or orphaning resulting from the disappearance of one pole in the duality of world and inhabitant—the beings whose world it is. In our metaphysical tradition, this being tends to be the “human,” whether called Homo sapiens or Dasein. The disappearance may be due to either physical extinction or one pole’s absorption by the other, which leads to a change in the persisting one. We could schematically present this as an opposition between a “world without us,” that is, a world after the end of the human species, and an “us without world,” a humanity bereft of world or environment, a persistence of some form of humanity or subjectivity after the end of the world.

But to think the future disjunction of world and inhabitant inevitably evokes the origin of its present, precarious conjunction. The end of the world projects backward a beginning of the world; the future fate of humankind transports us to its emergence. The existence of a world before us, although regarded as a philosophical challenge by some (if Meillassoux’s subtle argument is to be believed ), seems easy enough for the average person to imagine. The possibility of an us before the world, on the other hand, is less familiar to the West’s mythological repertoire.

Yet it is a hypothesis explored in several Amerindian cosmogonies. It finds itself conveniently summarized in the commentary that opens a myth of the Yawanawa, a people of Pano-speakers from the western Amazon: “The myth’s action takes place in a time in which ‘nothing yet was, but people already existed.’” The variation of the Aikewara, a Tupian-speaking people who live at the other end of the Amazon, adds a curious exception: “When the sky was still very close to the Earth, there was nothing in the world except people—and tortoises!”

At first, then, everything was originally human, or rather, nothing was not human (except for tortoises, of course, according to the Aikewara). A considerable number of Amerindian myths—as well as some from other ethnographic regions—imagine the existence of a primordial humankind, whether fabricated by a demiurge or simply presupposed as the only substance or matter out of which the world could have come to be formed.

These are narratives about a time before the beginning of time, an era or eon that we could call “pre-cosmological.” These primordial people were not fully human in the sense that we are, since, despite having the same mental faculties as us, they possessed great anatomic plasticity and a certain penchant for immoral conduct (incest, cannibalism). After a series of exploits, some groups of this primordial humankind progressively morphed—either spontaneously or due to the action of a demiurge—into the biological species, geographical features, meteorological phenomena, and celestial bodies that comprise the present cosmos. The part that did not change is the historical, or contemporary, humankind.

One of the best illustrations of this general type of cosmology is described in great detail in the autobiography of Yanomami shaman and political leader Davi Kopenawa. We could also recall ideas from the Ashaninka (Campa), an Arawak people both geographically and culturally distant from the Yanomami:

Campa mythology is largely the story of how, one by one,the primal Campa became irreversibly transformed into the first representatives of various species of animals and plants, as well as astronomical bodies or features of the terrain … The development of the universe, then, has been primarily a process of diversification, with mankind as the primal substance out of which many if not all of the categories of beings and things in the universe arose, theCampa of today being the descendants of those ancestralCampa who escaped being transformed.Complete text here

No comments:

Post a Comment