Last week, the Doomsday Clock moved to three minutes from midnight. Yet, while it is intended to measure the closeness to total destruction, "what the clock really measures is worry—that is, how worried members of the Bulletin’s Science and Security Board are about the state of the world."

Measurement of cataclysm is intimately related to the sense of it, in other words, how unmeasureable it is. While previous geological time periods have been measured, let thousands of years after they existed, the anthropocene is defined by its presentness, and by extension its unmeasurability.

http://blogs.scientificamerican.com/observations/it-s-doomsday-clock-time-again/ http://thebulletin.org/overview

"This mechanization of the body—a precursor and template

for the ongoing reconceptualization of the self in terms of quantities

alone—reflects how our bodies have become products, rather than agents,

of a culture of busyness and rationality that glorifies productivity.

Scientific discourses have succeeded in masking the way we’ve been

clocked in and can no longer clock out."

http://thenewinquiry.com/essays/the-clock-inside-us/

Sunday, January 31, 2016

Deleuze and the Anthropocene edited collection

Hi all,

I am in a Deleuze and Guattari group on Facebook, and someone named Alexander Stingl recently posted asking if anyone would be interested in contributing to an edited collection on Deleuze and the Anthropocene. If anyone is considering writing about this topic for their final paper, it may be worth looking into adding to the collection.

If you are interested in learning more about this, email Alexander Stingl at:

nomadicscholarship@gmail.com

Apparently, there is a special issue of "Deleuze Studies" coming out on the Anthropocene this year as well.

I am in a Deleuze and Guattari group on Facebook, and someone named Alexander Stingl recently posted asking if anyone would be interested in contributing to an edited collection on Deleuze and the Anthropocene. If anyone is considering writing about this topic for their final paper, it may be worth looking into adding to the collection.

If you are interested in learning more about this, email Alexander Stingl at:

nomadicscholarship@gmail.com

Apparently, there is a special issue of "Deleuze Studies" coming out on the Anthropocene this year as well.

Leviathan (2012)

The film Leviathan (2012) is a documentary/experimental/ethnographic piece about the organic experience and various perspectives and practices of a fishing boat off the coast of New England.

Captured with various GoPro cameras that get flung, dragged and dunked along with the various parts of the fishing trawler (flung with the fishing net into the water, dragged through the fish cleaning equipment with some of the catchings, sunk into the ocean with the discarded leftovers, to name a few). The film has been talked about for its sensory, visceral aesthetic and it takes great pains to construct perspectives that exist outside of the typical human perspectives and demarcations between animal, human, nature, and culture. The film asks the question of what it is like to be a barnacle on the stern of the ship, or a rope, straining under the weight of the sea.

In this sense, I think the film is a useful visual-sensory exploration of processes of negotiating and overlapping nature and life, as discussed in Whitehead last week.

Unfortunately, the trailer does not demonstrate this exploration very well, as it attempts to cast more of a rigid narrative and structure onto the film than exists in the feature. I recommend watching the film!

Captured with various GoPro cameras that get flung, dragged and dunked along with the various parts of the fishing trawler (flung with the fishing net into the water, dragged through the fish cleaning equipment with some of the catchings, sunk into the ocean with the discarded leftovers, to name a few). The film has been talked about for its sensory, visceral aesthetic and it takes great pains to construct perspectives that exist outside of the typical human perspectives and demarcations between animal, human, nature, and culture. The film asks the question of what it is like to be a barnacle on the stern of the ship, or a rope, straining under the weight of the sea.

In this sense, I think the film is a useful visual-sensory exploration of processes of negotiating and overlapping nature and life, as discussed in Whitehead last week.

Unfortunately, the trailer does not demonstrate this exploration very well, as it attempts to cast more of a rigid narrative and structure onto the film than exists in the feature. I recommend watching the film!

Saturday, January 30, 2016

Anthropogenesis: Origins and Endings in the Anthropocene

Yusoff, K.,(2016) Theory, Culture, & Society, 33(2), pp. 3-28

(Got the rest of the paper to be sent upon request)

(Got the rest of the paper to be sent upon request)

Friday, January 29, 2016

Capitalism as Ecology and the Anthropocene

A friend of mine posted this article on Facebook called "Is Capitalism an Ecological System?" about a recent book by philosopher Jason W. Moore, Capitalism in the Web of Life: Ecology and the Accumulation of Capital. I thought it was relevant to some of the discussions we've been having in class, so I thought I would share it.

As the article delineates, Moore's book proposes that rather than understanding 'capitalism' as an ideology, political formation or economic structure, it should be conceived of as a "a way of organizing nature".

I haven't read the book, but the article goes on to say that by considering capitalism a system for organizing nature, Moore concludes that, "Nature can neither be saved nor destroyed, only transformed.”

Following this, the author of the article somewhat hopefully asserts, "If we accept that nature is not a timeless background to capitalism, but instead that “historical natures” are produced by and products of modes of production, then it becomes increasingly clear that historical natures and their reproduction are not incidental to accumulation. Natures are the condition of its possibility."

Besides the fact that I find it quite surprising that this author seems to imply Moore's book is responsible for the revelation that capitalism has had a significant impact on "the environment", or that nature holds potential for possibility, it is this concept of "historical nature" that is closely related to, if not essentially synonymous with (on a smaller, less encompassing scale), the anthropocene, and which I would like to draw out.

I have several thoughts on this terminology, 'historical nature'. For starters, it imposes a fallacious division between history and nature, demonstrating that Moore's theory is fundamentally anthropocentric (at least as far as I am able to glean from the article's short summary), predicated as it is on the longstanding dichotomy between human/nature or human/environment and whole litany of related binary opposites such as civilization/nature, subject/object, progress/nature etc. etc. ad infinitum. I found last week's Whitehead readings helpfully disrupted this longstanding dichotomy by employing terms such as "human animals". Unfortunately, Moore's theory does not share this ethos and as such it does not productively account for humans as an integral part of 'nature/the environment', destructive in many/most manifestations though they have been.

Despite the theory's shortcomings, I find thinking of capitalism as an ecology is helpful. There is something about Moore's notion that capitalism is able to exert mastery over 'nature' to such an extent that it is able to organize that seems wrong to me. I think what many conceive of as a strict opposition is actually an ongoing process of negotiation, think, for instance, of a tree that that has grown around a telephone line. Nature and capitalism are not separate entities, they are intimately intertwined, and always already interacting.

To write or think that the relation between capitalism and nature is unilateral or weighted in such a way that the former is actually able to systematically control the latter seems nonsensical to me. But the concept of capitalism as an ecology, as a nexus of relations that is inextricable from the organization of nature, not responsible for it, that I think is a less anthropocentric and more potentially fruitful (no pun intended...okay maybe a little) way to think about how to move toward a more mutually beneficial negotiation.

As the article delineates, Moore's book proposes that rather than understanding 'capitalism' as an ideology, political formation or economic structure, it should be conceived of as a "a way of organizing nature".

I haven't read the book, but the article goes on to say that by considering capitalism a system for organizing nature, Moore concludes that, "Nature can neither be saved nor destroyed, only transformed.”

Following this, the author of the article somewhat hopefully asserts, "If we accept that nature is not a timeless background to capitalism, but instead that “historical natures” are produced by and products of modes of production, then it becomes increasingly clear that historical natures and their reproduction are not incidental to accumulation. Natures are the condition of its possibility."

Besides the fact that I find it quite surprising that this author seems to imply Moore's book is responsible for the revelation that capitalism has had a significant impact on "the environment", or that nature holds potential for possibility, it is this concept of "historical nature" that is closely related to, if not essentially synonymous with (on a smaller, less encompassing scale), the anthropocene, and which I would like to draw out.

I have several thoughts on this terminology, 'historical nature'. For starters, it imposes a fallacious division between history and nature, demonstrating that Moore's theory is fundamentally anthropocentric (at least as far as I am able to glean from the article's short summary), predicated as it is on the longstanding dichotomy between human/nature or human/environment and whole litany of related binary opposites such as civilization/nature, subject/object, progress/nature etc. etc. ad infinitum. I found last week's Whitehead readings helpfully disrupted this longstanding dichotomy by employing terms such as "human animals". Unfortunately, Moore's theory does not share this ethos and as such it does not productively account for humans as an integral part of 'nature/the environment', destructive in many/most manifestations though they have been.

Despite the theory's shortcomings, I find thinking of capitalism as an ecology is helpful. There is something about Moore's notion that capitalism is able to exert mastery over 'nature' to such an extent that it is able to organize that seems wrong to me. I think what many conceive of as a strict opposition is actually an ongoing process of negotiation, think, for instance, of a tree that that has grown around a telephone line. Nature and capitalism are not separate entities, they are intimately intertwined, and always already interacting.

To write or think that the relation between capitalism and nature is unilateral or weighted in such a way that the former is actually able to systematically control the latter seems nonsensical to me. But the concept of capitalism as an ecology, as a nexus of relations that is inextricable from the organization of nature, not responsible for it, that I think is a less anthropocentric and more potentially fruitful (no pun intended...okay maybe a little) way to think about how to move toward a more mutually beneficial negotiation.

Twilight of the Anthropocene Idols

Following on from Theory and the Disappearing Future, Cohen, Colebrook and Miller turn their attention to the eco-critical and environmental humanities’ newest and most fashionable of concepts, the Anthropocene. The question that has escaped focus, as “tipping points” are acknowledged as passed, is how language, mnemo-technologies, and the epistemology of tropes appear to guide the accelerating ecocide, and how that implies a mutation within reading itself—from the era of extinction events.

Only in this moment of seeming finality, the authors argue, does there arise an opportunity to be done with mourning and begin reading. Drawing freely on Paul de Man’s theory of reading, anthropomorphism and the sublime, Twilight of the Anthropocene Idols argues for a mode of critical activism liberated from all-too-human joys and anxieties regarding the future. It was quite a few decades ago (1983) that Jurgen Habermas declared that ‘master thinkers had fallen on hard times.’ His pronouncement of hard times was premature. For master thinkers it is the best of times. Not only is the world, supposedly, falling into a complete absence of care, thought and frugality, a few hyper-masters have emerged to tell us that these hard times should be the best of times. It is precisely because we face the end that we should embrace our power to geo-engineer, stage the revolution, return to profound thinking, reinvent the subject, and recognize ourselves fully as one global humanity. Enter anthropos.

Wednesday, January 27, 2016

Phytocene, not Anthropocene

Phytocene

Because "plants are a force and a power to be reckoned with." An article from Prof. Natasha Myers, associate professor in the Department of Anthropology at York University.

Photosynthesis is my keyword for this era that we keep calling the

Anthropocene. Photosynthesis circumscribes a complex suite of

electrochemical processes that spark energy gradients across densely

folded membranes inside the symbiotic chloroplasts of green beings

(Margulis and Sagan 2000). Textbook diagrams familiar from high-school

biology class are simplistic renderings of that utterly magical, totally

cosmic alchemical process that tethers earthly plant life in reverent,

rhythmic attention to the earth’s solar source. The photosynthetic

ones—those green beings we have come to know as cyanobacteria, algae,

and plants—are sun worshippers and worldly conjurers. Lapping up

sunlight, inhaling carbon dioxide, drinking in water, and releasing

oxygen, they literally make the world. Pulling matter out of thin air,

they teach us the most nuanced lessons about mattering and what really matters: their beings and doings have enormous planetary consequences.

To name photosynthesis as a keyword for these dire times serves as a crucial reminder that we are not alone. There are other epic and epochal forces in our midst. Photosynthetic organisms form a biogeochemical force of a magnitude we have not yet properly grasped. Over two billion years ago, photosynthetic microbes spurred the event known today as the oxygen catastrophe, or the great oxidation. These creatures dramatically altered the composition of the atmosphere, choking out the ancient anaerobic ones with poisonous oxygen vapors (Margulis 1998). Indeed, we now live in the wake of what should be called the Phytocene. These green beings have made this planet livable and breathable for animals like us. We thrive on plants’ wily aptitude for chemical synthesis. All cultures and political economies, local and global, turn around plants’ metabolic rhythms. Plants make the energy-dense sugars that fuel and nourish us, the potent substances that heal, dope, and adorn us, and the resilient fibers that clothe and shelter us. What are fossil fuels and plastics but the petrified bodies of once-living photosynthetic creatures? We have thrived and we will die, burning their energetic accretions. And so it is not an overstatement to say that we are only because they are. The thickness of this relation teaches us the full meaning of the word interimplication.

...

Whole article:

http://culanth.org/fieldsights/790-photosynthesis

Because "plants are a force and a power to be reckoned with." An article from Prof. Natasha Myers, associate professor in the Department of Anthropology at York University.

Photosynthesis

by Natasha Myers

This article is part of the series Lexicon for an Anthropocene Yet Unseen

To name photosynthesis as a keyword for these dire times serves as a crucial reminder that we are not alone. There are other epic and epochal forces in our midst. Photosynthetic organisms form a biogeochemical force of a magnitude we have not yet properly grasped. Over two billion years ago, photosynthetic microbes spurred the event known today as the oxygen catastrophe, or the great oxidation. These creatures dramatically altered the composition of the atmosphere, choking out the ancient anaerobic ones with poisonous oxygen vapors (Margulis 1998). Indeed, we now live in the wake of what should be called the Phytocene. These green beings have made this planet livable and breathable for animals like us. We thrive on plants’ wily aptitude for chemical synthesis. All cultures and political economies, local and global, turn around plants’ metabolic rhythms. Plants make the energy-dense sugars that fuel and nourish us, the potent substances that heal, dope, and adorn us, and the resilient fibers that clothe and shelter us. What are fossil fuels and plastics but the petrified bodies of once-living photosynthetic creatures? We have thrived and we will die, burning their energetic accretions. And so it is not an overstatement to say that we are only because they are. The thickness of this relation teaches us the full meaning of the word interimplication.

...

Whole article:

http://culanth.org/fieldsights/790-photosynthesis

Tuesday, January 26, 2016

Nature, three lecture courses: Merleau-Ponty in discussion with Whitehead

Vallier, Robert. Course Notes from the Collège de France by Maurice Merleau-Ponty. Evanston, IL. Northwestern University Press: 2003.

I have a fondness for Merleau-Ponty. 1950's are a long ways away. I enjoy digging in archival notes.

I found a recent-ish book review from Leonard Lawlor (2006) in the Human Studies journal, putting in conversation some, Merleau-Ponty to Whitehead's principles of Nature. I found Lawlor to be efficient at comparing and distilling Merleau'Ponty's last courses on Nature. I also am doing a tad of research on Merleau-Ponty's unfinished book The Visible and The Invisible. From a few versions I read fast through, in English, I grit my teeth. The writings are tainted with opinions, pompous explanations, tedious strings of too much letters in one sentence. I found Lawlor a useful and clear complement to both our past class with Erin Manning on Whitehead and Nature, and explaining some, of the intent behing The Visible and The Invisible.

If you are like me, I find comparisons quite useful to remember specific notions. What does it say about my learning mode? Enjoy the review read!

I put the whole article up on my Google Drive

Review - Merleau-Ponty - Principle of Nature

I have a fondness for Merleau-Ponty. 1950's are a long ways away. I enjoy digging in archival notes.

I found a recent-ish book review from Leonard Lawlor (2006) in the Human Studies journal, putting in conversation some, Merleau-Ponty to Whitehead's principles of Nature. I found Lawlor to be efficient at comparing and distilling Merleau'Ponty's last courses on Nature. I also am doing a tad of research on Merleau-Ponty's unfinished book The Visible and The Invisible. From a few versions I read fast through, in English, I grit my teeth. The writings are tainted with opinions, pompous explanations, tedious strings of too much letters in one sentence. I found Lawlor a useful and clear complement to both our past class with Erin Manning on Whitehead and Nature, and explaining some, of the intent behing The Visible and The Invisible.

If you are like me, I find comparisons quite useful to remember specific notions. What does it say about my learning mode? Enjoy the review read!

I put the whole article up on my Google Drive

Review - Merleau-Ponty - Principle of Nature

Principle of Nature

Maurice Merleau-Ponty,

France, compiled and the French by Robert

2003, pp. xx, 313.

France, compiled and the French by Robert

2003, pp. xx, 313.

The

Nature,

with notes by

Course Notes from

the Coll?ge de

translated from

University Press,

University Press,

Dominique S?glard,

Vallier. Evanston: Northwestern

The publication of Nature, which presents in English three lecture courses

that Merleau-Ponty taught at the Coll?ge de France (during the academic

years 1956-57, 1957-58, and 1959-60), allows us finally to lay a rumor to rest. For decades Merleau-Ponty scholars have been saying that out of all

the courses Merleau-Ponty taught at the Coll?ge de France during the Fifties, the courses on nature give us the clearest insight into his final

thought. This rumor, we can now confirm, turns out to be true. These lecture courses on nature are so important that they rival Merleau-Ponty's

years 1956-57, 1957-58, and 1959-60), allows us finally to lay a rumor to rest. For decades Merleau-Ponty scholars have been saying that out of all

the courses Merleau-Ponty taught at the Coll?ge de France during the Fifties, the courses on nature give us the clearest insight into his final

thought. This rumor, we can now confirm, turns out to be true. These lecture courses on nature are so important that they rival Merleau-Ponty's

The Visible and the Invisible, or, more precisely, they comple

ment The Visible and the Invisible. While the publication of Heidegger's

lecture course called The Basic Problems of Phenomenology gave us a sense of what Part Two ofBeing and Time would have looked like, the publication ofNature gives us a sense of what "the propaedeutic" for The Visible and the Invisible would have looked like (204). They prepare us to remember, as

Merleau-Ponty says in The Visible and the Invisible, the originary sense of being as the "jointure" (or balance) between the visible and the invisible.

All three courses are simply called "The Concept of Nature." The first, however, falls into two parts. The first part, which is called "Study of the

Variations of the Nature," lays out the concept's philosophical evolution in the modern period, from Descartes to Husserl, by way of Kant,

Schelling, and Bergson. The modern tradition defines nature as "a

product," as "pure exteriority" (9); nature, according toMerleau-Ponty,

loses the interiority and orientation, the finality or teleology that the concept still retained from the Stoics up to the Renaissance. In the

modern epoch, nature becomes a machine; it is spread out (partes extra

partes) as a pure object before the pure understanding, and interiority now resides in God who is the artisan of the machine. Because this

conception requires an artisan, Merleau-Ponty calls it anthropomorphic (10). For Merleau-Ponty, modern science still retains this "Cartesian"

lecture course called The Basic Problems of Phenomenology gave us a sense of what Part Two ofBeing and Time would have looked like, the publication ofNature gives us a sense of what "the propaedeutic" for The Visible and the Invisible would have looked like (204). They prepare us to remember, as

Merleau-Ponty says in The Visible and the Invisible, the originary sense of being as the "jointure" (or balance) between the visible and the invisible.

All three courses are simply called "The Concept of Nature." The first, however, falls into two parts. The first part, which is called "Study of the

Variations of the Nature," lays out the concept's philosophical evolution in the modern period, from Descartes to Husserl, by way of Kant,

Schelling, and Bergson. The modern tradition defines nature as "a

product," as "pure exteriority" (9); nature, according toMerleau-Ponty,

loses the interiority and orientation, the finality or teleology that the concept still retained from the Stoics up to the Renaissance. In the

modern epoch, nature becomes a machine; it is spread out (partes extra

partes) as a pure object before the pure understanding, and interiority now resides in God who is the artisan of the machine. Because this

conception requires an artisan, Merleau-Ponty calls it anthropomorphic (10). For Merleau-Ponty, modern science still retains this "Cartesian"

concept of nature, and its prevalence in modern science is why the

Cartesian concept still "explains us" (8). Part Two of the first course

examines modern science: "Modern Science and the Idea of Nature."

As already indicated, Merleau-Ponty claims in the first part that this concept of nature originates in Descartes. Nevertheless, and this is what

makes the first course so interesting, all the figures that Merleau-Ponty examines do not simply express the Cartesian or objectivistic conception of nature. All exhibit a kind of "strabism" or "diplopy" (127, 134). The "oscillation" that Merleau-Ponty locates in each figure means that none

in fact give us Merleau-Ponty's own position (55). Indeed, if we look at a text that is contemporaneous with the nature lectures, "Everywhere and

examines modern science: "Modern Science and the Idea of Nature."

As already indicated, Merleau-Ponty claims in the first part that this concept of nature originates in Descartes. Nevertheless, and this is what

makes the first course so interesting, all the figures that Merleau-Ponty examines do not simply express the Cartesian or objectivistic conception of nature. All exhibit a kind of "strabism" or "diplopy" (127, 134). The "oscillation" that Merleau-Ponty locates in each figure means that none

in fact give us Merleau-Ponty's own position (55). Indeed, if we look at a text that is contemporaneous with the nature lectures, "Everywhere and

Nowhere,"

presenting

we would have to say that Descartes comes

-

it. Descartes the Descartes of the Sixth Meditation

the problem that drives the modern philosophical

-

it. Descartes the Descartes of the Sixth Meditation

the problem that drives the modern philosophical

closest to

especially tradition

especially tradition

-

forward,

union of the body and soul implies that nature contains a "residue" that cannot be understood through the machine idea; it contains a "contin

forward,

union of the body and soul implies that nature contains a "residue" that cannot be understood through the machine idea; it contains a "contin

sets up

Merleau-Ponty.

to Merleau-Ponty, Yet, Descartes

to Merleau-Ponty, Yet, Descartes

that leads to

conceives of God

the problem

with which Merleau-Ponty himself grapples. The

that cannot be reduced to

Neither mechanism nor finalism are adequate to nature. For Descartes,

Neither mechanism nor finalism are adequate to nature. For Descartes,

gency" in its productions

teleology (83, 32).

the residue that cannot

cannot be understood. The relation to God here is very important for

cannot be understood. The relation to God here is very important for

resembles God whose ways also

It is precisely the idea of God as being infinite, according

be understood

the Cartesian conception of nature (8).

and nature in "separation" from one

God's infinity must be "mixed" inwith

course, Merleau-Ponty expresses this mixture by saying that nature "carries" us (44, the French verb is "por

ter"). Carrying us, nature is "larger." Therefore, as in "Everywhere and Nowhere," the laterMerleau-Ponty always stresses that the techniques of modern science, which are "smaller," have to be related back to nature.

God's infinity must be "mixed" inwith

course, Merleau-Ponty expresses this mixture by saying that nature "carries" us (44, the French verb is "por

ter"). Carrying us, nature is "larger." Therefore, as in "Everywhere and Nowhere," the laterMerleau-Ponty always stresses that the techniques of modern science, which are "smaller," have to be related back to nature.

another (66). For Merleau-Ponty,

nature (37). Repeatedly in the

So, in the second part of the first course, Merleau-Ponty

contemporary science, especially, contemporary physics. Even

examines

though it also

parti are only

"families of trajectories" (93). Despite overcoming the partes extra partes definition of nature, modern science, for Merleau-Ponty, cannot, how ever, elaborate a new conception of nature. This new conception can be

though it also

parti are only

"families of trajectories" (93). Despite overcoming the partes extra partes definition of nature, modern science, for Merleau-Ponty, cannot, how ever, elaborate a new conception of nature. This new conception can be

contemporary physics remains bound

to Cartesian ontology,

to wave-based mechanics,

criticizes this ontology (85). According

cles are no longer individuated or separated beings; there

cles are no longer individuated or separated beings; there

found only inWhitehead's philosophy. On the one hand, Whitehead,

for

Merleau-Ponty, makes modern science's self-critique explicit; he criticizes

the idea that each event in nature has a unique location in time and space.

On the other hand, and more importantly, for Merleau-Ponty, Whitehead

On the other hand, and more importantly, for Merleau-Ponty, Whitehead

seeks an element that is not

a part but

consists in

a whole (116). The whole,

pregnancy,

larger than any part,

translates Whitehead's

relations;

as "empi?tement"

as "empi?tement"

For Merleau-Ponty nature

present, giving the present

therefore, in Merleau-Ponty's

therefore, in Merleau-Ponty's

is the past that is still there affecting the

a kind of thickness and depth. Nature,

interpretation of Whitehead is a kind of

interpretation of Whitehead is a kind of

which is

Merleau

again

Ponty

(115),

writings. Even more, nature inWhitehead is a creative principle, an

"activity" that cannot be compared to the activity of consciousness or the mind (118). For Whitehead, nature is, of course, a "process", but Mer

leau-Ponty's French translation is "passage," a term that implies the past.

Ponty

(115),

writings. Even more, nature inWhitehead is a creative principle, an

"activity" that cannot be compared to the activity of consciousness or the mind (118). For Whitehead, nature is, of course, a "process", but Mer

leau-Ponty's French translation is "passage," a term that implies the past.

memory; this implies that it persists in its very "unfolding" (119, 120).

Nature is the "soil," "the earth," that not only carries us but also, as in

carries the future.

IS THERE ANY WORLD TO COME?

Here is a fragment of Danowski & Viveiros de Castro's 2014 book, "Há Mundo Por Vir? Ensaio sobre os meios e os fins" (Is there any World to come?) in which they discuss the Anthropocene and Amazonic indigenous cosmology (they have already passed through many "ends of the world"). Also, they make a good critique of the correlacionism discussion (Meillassoux, Brassier, etc.). It's in this text an passant but it's better discussed on the physical book (I'll transcribe or scan these pages in order to post them on the blog soon).

Deborah Danowski & Eduardo Viveiros de Castro

Translated by Rodrigo Nunes

Deborah Danowski & Eduardo Viveiros de Castro

Translated by Rodrigo Nunes

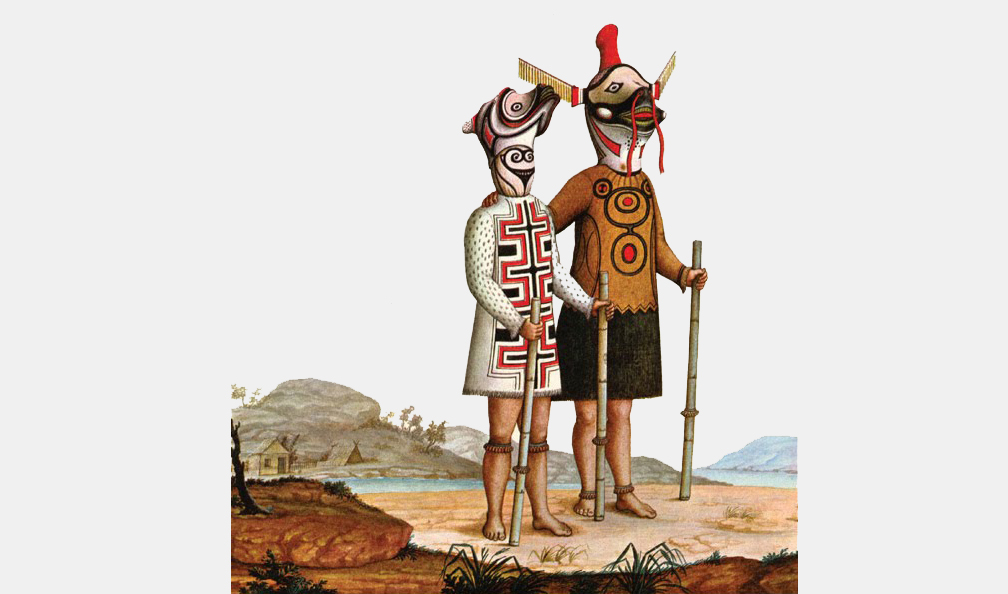

Drawing of two masked Jurupixuna Amerindians, a now extinct Amazonian tribe, registered during Alexandre Rodrigues Ferreira’s naturalist expedition to the Amazon (1783–93) for the Portuguese crown.

The problem of the end of the world is always formulated as a separation or divergence, a divorce or orphaning resulting from the disappearance of one pole in the duality of world and inhabitant—the beings whose world it is. In our metaphysical tradition, this being tends to be the “human,” whether called Homo sapiens or Dasein. The disappearance may be due to either physical extinction or one pole’s absorption by the other, which leads to a change in the persisting one. We could schematically present this as an opposition between a “world without us,” that is, a world after the end of the human species, and an “us without world,” a humanity bereft of world or environment, a persistence of some form of humanity or subjectivity after the end of the world.

But to think the future disjunction of world and inhabitant inevitably evokes the origin of its present, precarious conjunction. The end of the world projects backward a beginning of the world; the future fate of humankind transports us to its emergence. The existence of a world before us, although regarded as a philosophical challenge by some (if Meillassoux’s subtle argument is to be believed ), seems easy enough for the average person to imagine. The possibility of an us before the world, on the other hand, is less familiar to the West’s mythological repertoire.

Yet it is a hypothesis explored in several Amerindian cosmogonies. It finds itself conveniently summarized in the commentary that opens a myth of the Yawanawa, a people of Pano-speakers from the western Amazon: “The myth’s action takes place in a time in which ‘nothing yet was, but people already existed.’” The variation of the Aikewara, a Tupian-speaking people who live at the other end of the Amazon, adds a curious exception: “When the sky was still very close to the Earth, there was nothing in the world except people—and tortoises!”

At first, then, everything was originally human, or rather, nothing was not human (except for tortoises, of course, according to the Aikewara). A considerable number of Amerindian myths—as well as some from other ethnographic regions—imagine the existence of a primordial humankind, whether fabricated by a demiurge or simply presupposed as the only substance or matter out of which the world could have come to be formed.

These are narratives about a time before the beginning of time, an era or eon that we could call “pre-cosmological.” These primordial people were not fully human in the sense that we are, since, despite having the same mental faculties as us, they possessed great anatomic plasticity and a certain penchant for immoral conduct (incest, cannibalism). After a series of exploits, some groups of this primordial humankind progressively morphed—either spontaneously or due to the action of a demiurge—into the biological species, geographical features, meteorological phenomena, and celestial bodies that comprise the present cosmos. The part that did not change is the historical, or contemporary, humankind.

One of the best illustrations of this general type of cosmology is described in great detail in the autobiography of Yanomami shaman and political leader Davi Kopenawa. We could also recall ideas from the Ashaninka (Campa), an Arawak people both geographically and culturally distant from the Yanomami:

Campa mythology is largely the story of how, one by one,the primal Campa became irreversibly transformed into the first representatives of various species of animals and plants, as well as astronomical bodies or features of the terrain … The development of the universe, then, has been primarily a process of diversification, with mankind as the primal substance out of which many if not all of the categories of beings and things in the universe arose, theCampa of today being the descendants of those ancestralCampa who escaped being transformed.Complete text here

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)